Published: 07/12/2023

Updated: 11/11/2024

On a windy July day in 1910 a large crowd assembled on open land at Hengistbury Head near Bournemouth in excited anticipation of watching a display of the latest craze — nothing less than manned flight — not by hot-air balloon (that was old hat); but by the new-fangled contraption known as the aeroplane. However, what the eager crowd witnessed was a tragedy.

One of the day’s star attractions was the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls, already something of a household name, having very recently piloted his plane across the English Channel and back – without stopping – in the amazing time of 95 minutes, the first man ever to do so. Yes, the Frenchman Louis Bleriot had the honour of being the first man to fly the English Channel, but that was only one-way. Charles Rolls had to go one better, hence the return flight. To this day a statue of Rolls stands prominently in the centre of Monmouth, holding proudly a model of the plane which carried him into the history books.

But on this day, the weather wasn’t kind, and Rolls was urged to cancel his flight. Aeroplanes were still extremely flimsy and fragile things, little more than a bewildering tangle of wood and canvas, with the pilot fully exposed to the elements. Rolls refused to disappoint his admirers, and took to the skies in his Short-Wright No.5 biplane. It was his last flight; suddenly the tail-plane of his craft, perhaps not up to the strain of the gusting wind, broke off, the fuselage began to disintegrate, and airplane and pilot plunged to earth. He did not survive the impact; he died instantly or almost immediately of a fractured skull. Charles Rolls again entered the history books, this time as the first Briton ever to die in an aviation accident involving a powered aircraft.

He was only 32, and lies buried in a simple but prominent grave in the Monmouthshire churchyard of St Cadoc's, Llangattock-Vibon-Avel (Llangatwg Feibion Afel), close to the sprawling mansion The Hendre, which he loved, and which was ‘home’. Inside the church, which is a recent acquisition of the Friends, there is another memorial to Charles in the chancel. Professor Madeleine Gray has outlined the early history of this important church, almost entirely rebuilt in the mid-19th century thanks largely to the munificence of Charles Rolls’ father, the 1st Lord Llangattock.

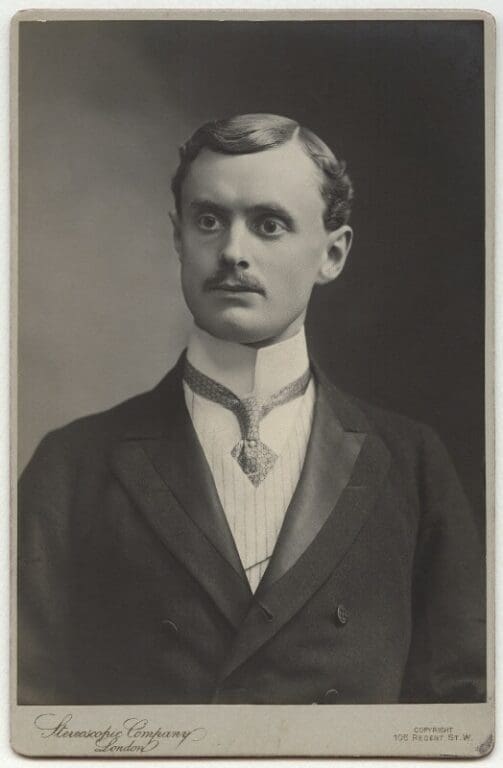

The Honorable Charles Stewart Rolls, © National Portrait Gallery, London (published under a Creative Commons license)

There was much more to Charles Rolls, of course, than an aviation pioneer. Born in 1877, he was the third son of John Allan Rolls, the first Baron Llangattock and head of the Rolls family, who were local landowners on a massive scale in this area of north Monmouthshire. During the 19th century, using the architects T H Wyatt, Henry Pope and Aston Webb, they laid out their enormous house, created a deer-park and a school, built a second house (Llangattock Manor), and rebuilt the church, employing the talents of Cox & Son to decorate the interior, and three of the leading stained-glass manufacturers of the day, to adorn the interior.

This, then, was all familiar territory to Charles Rolls, when he was home from Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, from which he graduated in 1895, significantly in mechanical and applied science. Significantly, for he was already in love with another late 19th-century invention: the motorcar. In 1896 he bought his first car, said to be one of the first three in Wales (whose were the other two, I wonder?). When the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George V and Queen Mary) visited The Hendre in 1900, Charles took them for what was probably their first ever ride in a motorcar. By 1903 he could see that the car was the coming thing, and, borrowing £6000 from his father, he set up one of Britain’s first dealerships in Fulham, importing the latest models from France and Belgium.

Importing cars was one thing, but in Rolls’ fertile brain, it was a short step to manufacturing a ‘home-grown’ variety. Enter another enthusiast, one Henry Royce; by 1904 they had forged a formal partnership, and before the end of that year the very first Rolls-Royce left the production line. The era of the luxury car had arrived, with all its stylish design and thoroughgoing elegance. Whether Rolls ever envisaged the mass production of the motor industry, and the clogged and polluted roads of less than a century after his untimely death is another question.

Rolls was a restless spirit. By 1907, his attention was already being drawn in another direction: the conquest of the air. Initially, he attempted to interest his partner in engines for the new airplanes, but with little success; Henry Royce (or Sir Henry as he ultimately became) preferred to stick with the motorcar. It seems to have resulted in some estrangement between the two young men, but who is to say that Rolls was not prescient? Rolls-Royce’s contribution to the aerospace industry was one of the great industrial success stories of the 20th century.

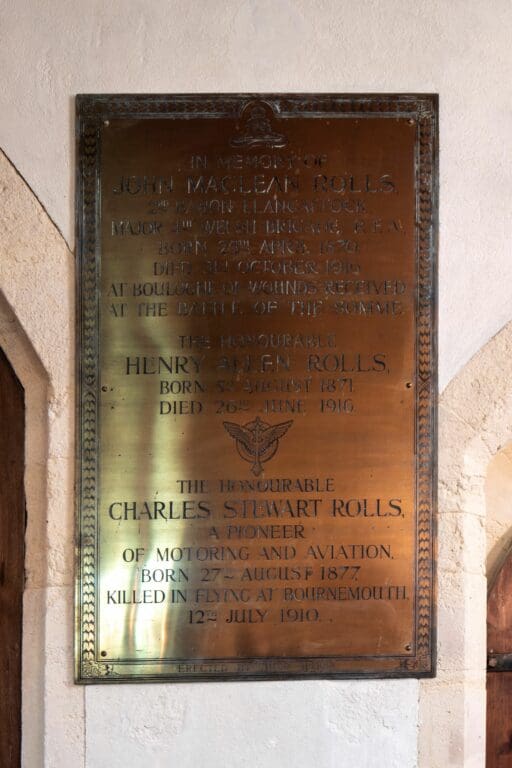

The direct line of the Rolls family is no more, and the title ‘Baron Llangattock’ is extinct; the second and last holder of it, Charles’ oldest brother John, perished in the carnage of the First World War in 1916, and his middle brother Henry died the same year of heart failure1. Their sister Eleanor, a pioneer in women’s engineering, and a motoring, ballooning and aviation enthusiast herself, did not qualify for the title, though she inherited the estate and married a baronet, becoming Lady Shelley-Rolls. Henry and Eleanor are also buried at Llangattock-Vibon-Avel, and a brass plaque dedicated to all three Rolls brothers can be seen in the chancel.

The great mansion of The Hendre is now a Golf Club. But do visit St Cadoc’s Church, serene and rather isolated, pass through the lych-gate given by the Rolls-Royce Company, contemplate the tall but simple cross over the grave of the pioneer aviator, and enjoy the rich and peaceful interior of the church he knew so well.

And don’t forget to journey to nearby Monmouth, historic and bustling market town, and birthplace of another significant figure in English history, King Henry V. The statue of the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls, complete with his plane, stands proud on its plinth before the Shire Hall in Agincourt Square. The statue is the work of Sir W Goscombe John; the plinth, complete with reliefs of balloon, racing car (yes, Rolls was a devotee of that sport, too) and biplane, designed by Aston Webb. Above, secure in his niche in the façade of the Shire Hall, Henry V gazes down upon him.