Published: 17/12/2021

Updated: 01/03/2022

Andrew Gant is a composer, choirmaster, church musician, university teacher and writer. He has directed many leading choirs including The Guards’ Chapel, Worcester College Oxford, and Her Majesty’s Chapel Royal. He lectures in Music at St Peter’s College in Oxford and is the author of several books on the history of music, including Christmas Carols and O Sing Unto the Lord.

You can travel a long way without going very far.

Within about sixty miles of where I live in Oxford stand a whole series of beautiful, evocative church buildings, now in the loving care of Friends of Friendless Churches, whose stones and corbels have heard the echo of perhaps a thousand Christmases.

What did they hear?

St John the Baptist’s, Allington, in Wiltshire, features a small segment of a Norman door arch, with the familiar geometric patterning used by the masons who came over the water with the Conqueror almost a millennium ago. Another who travelled with William and his invading army was his kinsman Osmund, who became Bishop of Salisbury and helped found what is now the windy ruin of Old Sarum on its hilltop just a few miles from Allington. Osmund helped codify the “Use of Sarum”: a manual of liturgical practice for the church’s year. Its music was plainsong; single-lined chant of greater or lesser complexity depending on the resources available and the importance of the feast or saint’s day in the calendar. By Osmund’s day Christmas was a sufficiently important fixture that his cousin William was actually crowned on Christmas Day in Westminster Abbey.

Allington would certainly never have heard chanting of the magnificence managed by the monks of Westminster that Christmas, an educated elite immortalised alongside their monarch in the Bayeux Tapestry. At best, Allington’s priest might have sung the daily office on his own as he picked his way beneath that arch to the matins and mass of the birth of our Lord one wet Christmas a thousand years ago.

St Leonard’s, Spernall, in Warwickshire, has elements from many periods of history, like so many of our churches: the 12th-century nave, window tracery from the 13th and 14th centuries, some 15th century glass and a door from 1535. The year 1535 might sound like a distant historical place to us, a foreign country where they do things differently. But the date is significant. Just a year earlier Henry VIII had broken with Rome and made himself Head of the Church. For the remaining decade or so of his increasingly unstable and erratic reign that Church remained to a large extent unchanged in its observance, if not its governance: Catholic liturgies, in Latin, sung by trained initiates. At parish level that meant probably a chantry priest offering Mass to the local celebrity saint, together with the monks of the local religious house, and perhaps a couple of choirboys, destined for the tonsure themselves. It is unlikely that in a rural parish like Spernall they had the training, time or books to manage the increasingly elaborate polyphony of high-end composers based in the royal palaces of Windsor or St James’s, or the choral foundations of cathedrals and colleges like Oxford, Cambridge, Eton and Windsor — men like John Tavener, John Ludford, John Merbecke and Thomas Tallis.

Christmas at Spernall was not so grand. A beautiful miniature illustration from an antiphoner preserved at Ranworth in Norfolk shows the kind of music-making a well-run parish might have managed: two or three priests standing round a single music desk, reading from one book of plainsong. A little boy peers up at the inky pages, following the lead of his older fellow choristers, who had no doubt learned the same things themselves from the same book on the same lectern. Over time they have learnt to add a kind of primitive parallel harmony to the single line of music in front of them, one voice a fourth above, another a third below, making sweet chords known as “faburden”.

The church of the Assumption, Hardmead, Buckinghamshire looks like the picture-perfect English village church: the square tower, the white stone, the faded gravestones growing wonkily from the uneven grass, the obligatory yew tree. The dedication of this church hints at a lingering echo of the medieval cult of the Virgin Mary, the sort of idolatry which was meant to be swept away in the brave new world of the Reformation. Inside is a reminder that such historical divisions are never as neat as they may seem — a memorial to a member of the Catesby family, country-house Catholics and Gunpowder conspirators. For Christmas and its music, their significance is that the forces they unleashed led inexorably in time to the end of Christmas as a liturgical festival under Cromwell and the Puritans.

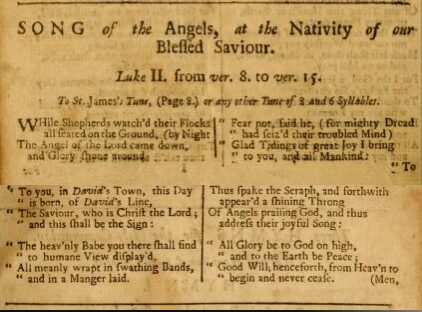

From ‘A New version of the Psalms of David : fitted to the tunes used in churches’ (1733)

By the time it came back with the restored Stuart monarchy, many other influences were beginning to hover around the tradition of Christmas music. Not far from Hardmead is the squat river-side church of St Mary Magdalene, Boveney, built to serve the eel-fishermen who plied the Thames outside its low walls. In the 18th century the church gained some simple wooden pews, where the parishioners would have sat in relative comfort, perhaps turning the pages of the new psalm book prepared by Nahum Tate and Nicholas Brady at the very end of the 17th century, with its metrical version of the song of the angels at the Nativity, designed to be sung to any one of hundreds of local tunes: “While Shepherds watched their Flocks by Night”.

In Waddesdon, also in Buckinghamshire, is a chapel built for an adherent of the Strict and Particular Baptists. They had little use for music; but non-conformism in its broader sense gave the English church its first and finest flowering of one of its chiefest glories: hymn-singing. Charles Wesley wrote very many hundreds of hymns, including the poem which, with a good deal of alteration by other hands, eventually became “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing”.

St John the Baptist’s, Allington — Victorian stained glass window by Heaton, Butler & Bayne

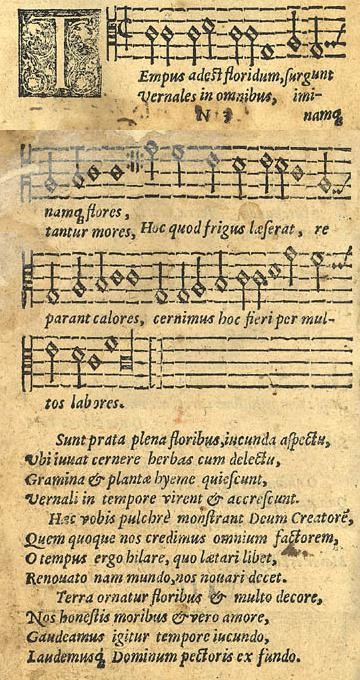

The later 19th century saw the rise of the high church Oxford Movement with its love of ritual, colour, elaboration and display. Musically, this was a fertile tradition, leading musicians like Thomas Helmore, Arthur Sullivan and many others to investigate folk song, plainsong, the music of the past and of other traditions, as well as composing and arranging their own distinctive repertoire which is so much a part of Christmas today: “God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen”, “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel”, “Good King Wenceslas”, “It came upon the midnight clear”, among many, many others. This Victorianisation of Christmas finds its analogue in the interiors of Pugin, Butterfield and Gilbert Scott, often, like the music, a conscious attempt to reach for the mood and manner of the medieval period, but with a sentimental accent which would have been quite foreign to the sturdy monks we met at Allington 500 years ago.

As well as its tiny fragment of Norman arch, Allington has some wonderfully vivid 19th-century stencils and wall decorations, super-imposing the flamboyance and colour of late-19th-century churchmanship directly onto a rougher medieval surface. This is exactly what Helmore was doing when he asked his fellow High Churchman and frequent collaborator John Mason Neale to compose the poem “Good King Wenceslas” to go with an ancient song about the coming of spring which he had found in a sixteenth-century school songbook from Finland.

Our friendless churches are not friendless now, and never have been. They have had many friends over the millennia. If we listen carefully we can hear their voices still.

The image of singing priests in the preview for this blog is from the St. Omer Psalter, British Library [Yates Thompson MS 14 f.103r]