Published: 19/05/2023

Updated: 05/08/2023

At St Cynhaearn’s, Ynyscynhaearn, a grand organ remains on the gallery. Made by the leading lights of organ-building in the early 1800s, this rare instrument has now fallen silent.

St Cynhaearn’s, reached by a long causeway, and dedicated to a 7th-century Welsh princeling who turned his back on the world and embraced the Religious Life, came to the FoFC in 2005. Visitors will find little enough of its long history, for it was all but rebuilt in 1830-32. What they will find is what Matthew Saunders described as feeling ‘like a late-Georgian estate church’. From its ‘three-decker’ pulpit, pews bearing the names of their owners, to the panelled western gallery, it breathes the air of the pre-Gothic Revival English society and Establishment Christianity which one might find in the pages of Mrs Gaskell’s Cranford.

If the pulpit dominates at one end, so, foursquare in the centre of the gallery, does the organ at the other. The respected Welsh church historian, Dr Roger Brown, in his 1997 Church & Clergy of Castle Caereinion, has drawn attention to the mid-19th-century craze for surpliced choirs of men and boys, occupying the chancel stalls, and displacing for ever the ‘singers’ assembled in the west gallery. The vibrant tradition of the ‘west gallery’, sometimes performing music by a talented local composer, gradually vanished, to be replaced, at least in parishes where public worship was in English, by the ‘Anglican chant’ of the Cathedral Psalter and the mainly anodyne tunes of Hymns Ancient & Modern (1861). Along with the choir came the organ, if the church was fortunate enough to have one, re-sited often in a purpose-built chamber off the chancel, where, inevitably, it could not be heard as its builder had intended. At Ynyscynhaearn, where no re-ordering of the interior has taken place, the organ remains in its gallery, its dark-wood case with its tapering ‘Gothick’ towers contrasting with the lighter wood of the surrounding panels.

William Madocks, c1812, National Library of Wales (public domain)

St Cynhaearn’s was not its original home. That was in a remarkable church built by a remarkable man. William Madocks (1773-1828) in 1798 bought land locally. He has been described as ’a romantic visionary’; he was also a hard-headed businessman. His land was on one of the main routes to Ireland, so in about 1800, in the midst of the Napoleonic wars, he first set about building an immense embankment, which reclaimed some 1000 acres of unusable land. It still carries the A487 road to Bangor and thence to Holyhead. Some five years later he built the model town, appropriately called Tremadoc (Tremadog). A church here soon followed, and probably it was here our organ had its first home. It came to St Cynhaearn’s sometime later, perhaps to be replaced by a more powerful instrument. It was bought by a Mrs Walker for £30, probably sometime after 1832, as before then there was nowhere suitable to put it. A good thing too as it transpired, for Tremadoc Church closed in 1995 and is now offices.

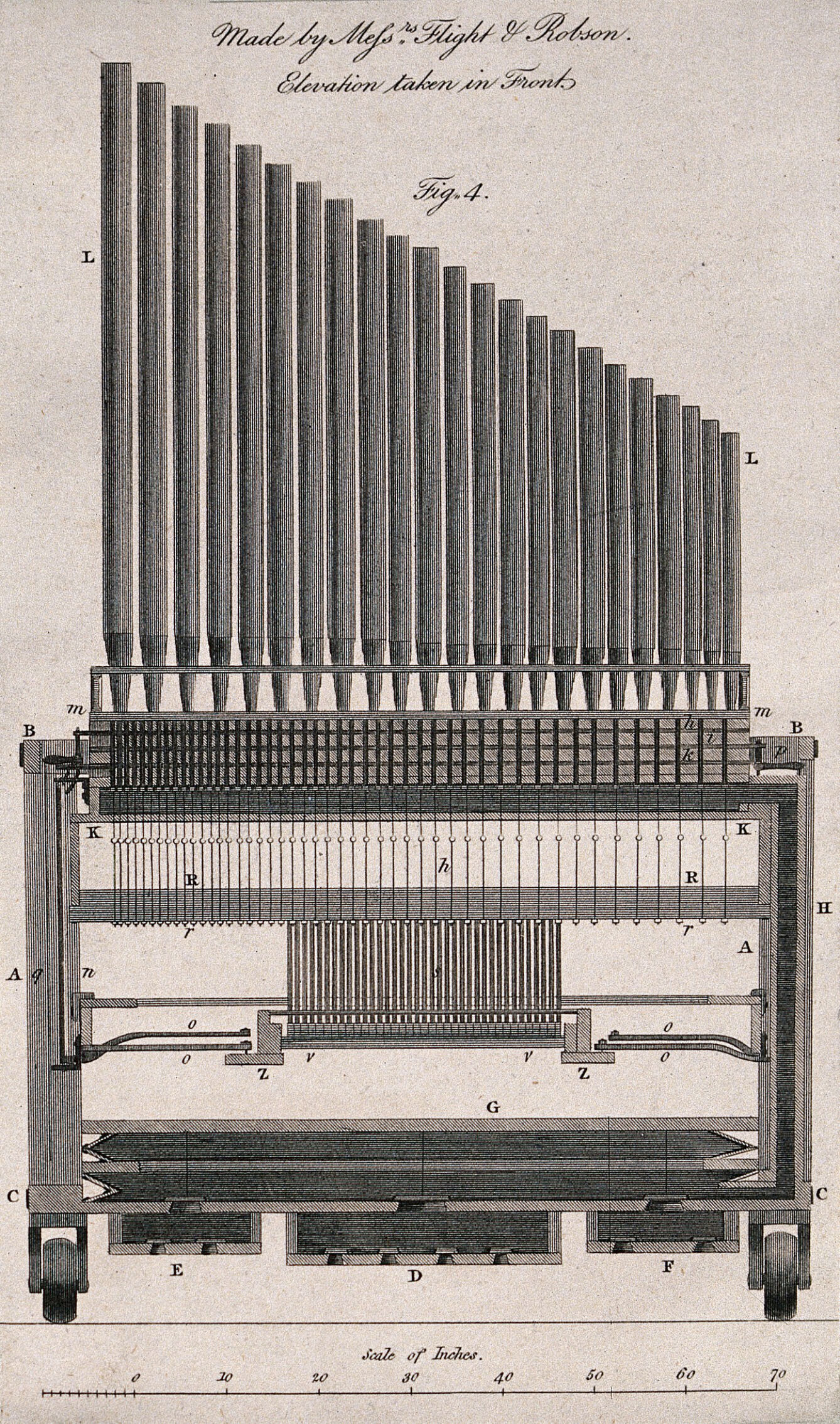

Thus Ynyscynhaearn became possessed of one of the treasures of 19th-century organ-building, for it is the work of Flight & Robson. Unlike ‘Father’ Willis, or Walker, or Compton, ‘Flight & Robson’ is no longer a household word in the organ world, but in their day the partners were renowned for their mechanical skills and innovation. Benjamin Flight (c.1767-1847) and Joseph Robson (c.1765-1846) entered into partnership in 1806, and set up their works in St Martin’s Lane, London. Both were experienced organ-builders – Robson is described as ‘Organ Builder to George IV’ (the king himself played the cello and the fortepiano) – so if a date for our instrument is circa 1811, then it dates from fairly early in their partnership.

Portrait of Benjamin Flight sitting by an organ, by George Dawe (public domain)

Their speciality was the chamber organ, suitable for substantial private houses; one such instrument survives at Calke Abbey, and another, with strikingly similar casework to ours, in a private house in Philadelphia, USA. But they could also build very small – the Victoria & Albert Museum owns a tiny instrument which could stand on a table – or absolutely huge; their famed ‘Apollonicon’ with five manuals, 45 stops (requiring some 1000 pipes), built in 1817 drew crowds of admirers, not the least because with its three barrels it was an ‘automatic playing machine’. When required, they could also be mechanically ingenious; witness the plans for the instrument they designed for the Earl of Kirkwall. Barrel organs, with their interchangeable barrels, were a godsend to parishes which found skilled organists hard to find. They provided a wide range of tunes suitable for congregational hymnody.

Sadly, the organ at Ynyscynhaearn is now ‘dumb’. It is sorely in need of restoration, which hopefully can be undertaken if and when funds permit – or when some kind benefactor comes forward with an open cheque-book and pledges to undertake the expense for us. Then we shall all be able to enjoy this rare instrument by Flight & Robson (and very few survive intact) as the builders intended, sounding from the west gallery. We can but hope.

Become a Friend

Receive our printed magazine — exclusive to members — and help us rescue more closed, historically important churches.