Published: 24/03/2023

Updated: 21/03/2024

17th-century Welsh poet Elen Gwdman has left a legacy of a single, passionate lament to unrequited love. Did an enigmatic vow she made in her verse hint at her entry into a convent, or even a brothel?

Elen Gwdman is something of a shooting star in the night sky of history; she flashes into and out of our sight for one brief moment in the early seventeenth century, and then is gone for ever. Her family and parentage is uncertain, as are the dates of her birth and death. Possibly, even probably, she was a scion of the Wood family of Tal-y-llyn in the heart of Anglesey, a wing of whose 16th- century house (Tal-y-llyn House) still survives a quarter of a mile from the simple, endearing little church which came to the Friends of Friendless Churches in 1999.

Welsh was the language of worship here, and of everyday speech, and it would have been Elen’s first language. Nothing has survived in her voice before 1616. Then she fell in love.

Plas Bodewryd

The object of her affection was one Edward Wynn of Bodewryd, a parish some distance to the north of Tal-y-llyn, whose splendid mansion, Plas Bodewryd, denotes a family of rather greater wealth and status than that of the Woods of Tal-y-llyn. Whether or not her affections were returned – she evidently thought so – we shall never know; in the end Edward found his bride elsewhere, in 1616 marrying the daughter of the Revd Edward Puleston, Vicar of Llanynys, head of a cadet branch of a prominent Caernarfonshire family. We know little of Pulestonhim, except that he was a confidant of John Salusbury of Rug, who was entangled in the abortive rebellion of the Earl of Essex in 1601. If Puleston’s loyalty to the Crown was thus in question, that of his son-in-law was not, for Edward Wynn served twice as Sheriff of his native county, in 1627-8 and 1634-5, before he died on 9th January 1638.

It was Edward Wynn’s marriage in 1616 which brings Elen to our notice, as it elicited her one surviving poem, a passionate lament for her lost love. In Cwynfon merch ifanc am ei chariad (A young girl's complaint about her sweetheart) she reveals herself as an experienced and talented poet; we can only regret that other works which once must have existed haven’t survived. In her lament she eschews the strict metres of traditional bardic poetry; intriguingly, the metre suggests that it could be sung to a melody that had a long shelf-life in Tudor and Stuart England — Rogero.

‘Rogero’ is a country dance tune which probably dates from the late sixteenth century, and attracted the attention of no less a person than the illustrious composer William Byrd (c.1540-1623) – who knew a good tune when he saw one – and made an arrangement of it for keyboard. As the name indicates, it originated elsewhere, as Aria di Ruggiero, in Italy, and was, appropriately, associated with a young gallant, which is evidently how Elen saw her Edward. Disappointment in love has long been a staple of the popular song, right down to our own day. In her poem (dare one say ‘pop song’?) being unsuccessful in love, she vows never to love another, and will travel to Rome and become a nun.

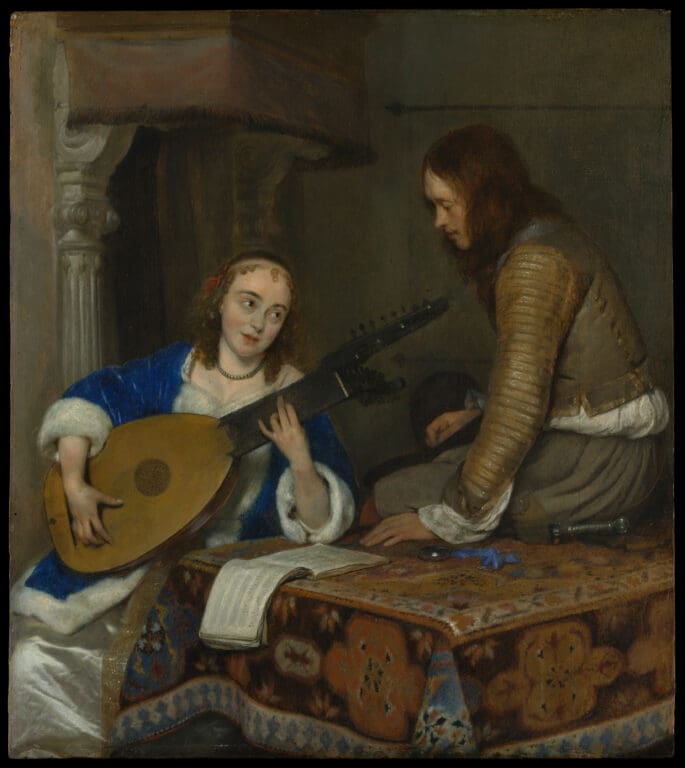

‘Rogero’ was included in several late 16th-century lute books. A Woman Playing the Theorbo-Lute and a Cavalier, Gerard ter Borch the Younger (metmuseum.org, public domain)

And here we have the enigma of Elen. Even in a poetic lament to make such a vow was a rather dangerous thing to do. In the reign of James I the Penal Laws against Catholics were still in force, and 1616 was scarcely a decade after the Gunpowder Plot of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators. It could have brought suspicion on Elen that she was a closet Catholic, a ‘church papist’ as they were called, with the ostracism at the very least that such an avowal could have brought upon her. A rather brave or rash thing to do.

But wait a moment; is there perhaps a rather darker interpretation of this vow? England’s monasteries and nunneries had all been dissolved the best part of a century before under Henry VIII, and by the date of Elen’s poem the word ‘nun’ had radically changed its meaning in popular parlance; it was slang for a harlot or at best a courtesan, just as the word ‘nunnery’ was a slang term for a brothel. After all, no less a person than Shakespeare had used it that way in Act 3 scene 1 of his Hamlet, first staged about 1600, in Hamlet’s angry command to Ophelia, ‘get thee to a nunnery’, which in today’s equivalent would be ‘get lost’ at its most polite, but would have been interpreted in rather cruder ways by Shakespeare’s ‘groundlings’. This is not to say that Elen had seen a performance of Hamlet; that is most unlikely, but she certainly could have been aware of the vulgar meaning of ‘nun’. Then again, ‘Rome-vill’ was contemporary slang for London itself. Was she in fact, heartbroken and probably angry at Edward Wynn’s jilting, as she may well have seen it, saying in her lament ‘very well, if I can’t have you, I’ll never truly love another or marry anyone else, and go off to the great metropolis – London – and become a harlot or courtesan, and that will teach you’. Fanciful and far-fetched? Very probably, but a seed of doubt once sown….Whatever is the true explanation, with her lament, Elen vanishes from history.

Cwynfon merch ifanc am ei chariad by Elen Gwdman is included with an English translation in Jane Stevenson & Peter Davidson (eds) ‘Early Modern Women Poets 1520-1700' (OUP 2001) pp. 157-60, and Nesta Lloyd (ed), ‘Seventeenth Century Poetry Anthology, Vol. 1’ (Barddas Publications, 1993).