Published: 14/10/2024

Updated: 14/10/2024

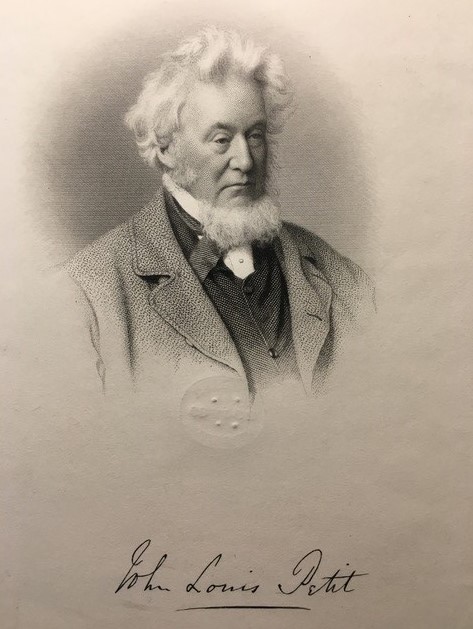

St Philip’s, Caerdeon, Gwynedd is an architectural anomaly. Aesthetically the church wouldn’t look out of place nestled in the Alpine foothills of the Mediterranean. This architectural individuality was the prime intention of the church’s architect Rev. John Louis Petit. In this article, Philip Modiano, founder of The Rev. Petit Society and author of Petit’s Tours of Old Staffordshire, explores Petit’s architectural and artistic career.

The Reverend John Louis Petit (1801–68) was a renowned artist and opponent of the Gothic revival during the mid-19th century. He painted in a style foreshadowing impressionism and exhibited his work widely in support of his architectural arguments.

He was a pioneer in arguing for the preservation of ancient churches, from 1841, when destructive restoration was at its peak, and later proposed original modernistic designs for church buildings.

However, he only completed one church himself, St Philip’s at Caerdeon, making it all the more valuable. Petit’s first book, Remarks on Church Architecture (1841) was highly praised by established media, and strongly criticised by the Ecclesiologist and the Cambridge Camden Society, since it diametrically opposed what they wanted to impose, calling for originality in new, preservation of the old and using foreign models. This and the battle over the restoration of St Mary’s, Stafford also in 1841 catapulted him to the centre of the debate for the next 25 years. For some he was the most important living author on architecture throughout the 1840s and even his opponents, such as Gilbert Scott, called him ‘highly gifted’.

A few Byzantine / Romanesque features from St Philip’s

By the 1850s the extreme positions of the Ecclesiologists had been softened. In his next book, Architectural Studies in France, (1854), Petit influenced architects to broaden their range to include the Angevin and Romanesque, while later he advocated a new modern style harmonising with the past, exhibiting designs at the Architectural Exhibition and provided designs to the Indian Missionary Society. During his life he designed his summer house at Upper Longdon, since destroyed, and St Philips, now Grade I protected: ‘highly unusual and distinctive … boldly original in its style and relationship with its landscape’ (British Listed Buildings).

Though Petit’s architectural views were strongly criticised, even his staunchest opponents admired his art. The popularity of his lectures and speeches was ensured by exhibiting 100 pictures at a time around the walls, for example at the Architectural Exhibition’s and the Architectural Museum’s lecture series. His distinctively pre-Impressionist style was, as with Gothic, in opposition to the prevailing, Pre-Raphaelite, fashion promoted by Ruskin. While Petit painted mainly medieval church sketches across Europe to support his arguments, he also completed wonderful broader landscapes and shipping pictures.

Caerdeon (1866) A watercolour by Rev. J L Petit Courtesy of The Rev. Petit Society

Caerdeon (1866) A watercolour by Rev. J L Petit Courtesy of The Rev. Petit Society

However, he never tried to sell his art. It mostly remained hidden for 150 years after his death, in the attic of a descendant. After his great niece died in 1953 the entire hoard was dumped at auction during the 1980s and 1990s and is widely dispersed. Slowly, however, research is starting to uncover and publicize the surprising range and quality of his finished works. Quite possibly this will be more accessible to future generations than his architectural arguments. Both were ahead of his time and are only now being rediscovered in the 21st century. The Reverend Petit is buried in the family vault in St Michael’s churchyard, Lichfield.

Thankfully Petit’s church has been vested to The Friends of Friendless Churches.

The Reverend Petit Society entirely supports this and any other initiative to recover the reputation of this major Victorian artist and architectural figure.