Published: 21/09/2021

Updated: 01/03/2022

John Gwin, a pillar of the community in 17th century Llangwm Uchaf, Monmouthshire, has left an extraordinary legacy.

His ‘Commonplace Book’, passed down over generations, is considered one of the most important sources for the history of medicine in Wales, and also opens a fascinating window into husbandry, family life, business practices, and local and community affairs set against a backdrop of significant political upheaval. As churchwarden for St. Jerome’s in the 1670s, Gwin dealt with ‘divers variances quarrels and debates’ among parishioners.

Tony Hopkins is a former Archivist of Gwent Archives. Together with Dr. Madeleine Gray of the University of South Wales, he is preparing to transcribe and publish John Gwin’s Commonplace Book, a remarkable record of 17th century life centred in Llangwm Uchaf, Monmouthshire. The book is planned for publication in late 2022. A historical trail that includes Llangwm Uchaf church and some of Gwin’s other landmarks is also being developed by Llangwm Historical Society.

This blog about the book is an abridged version of a lecture.

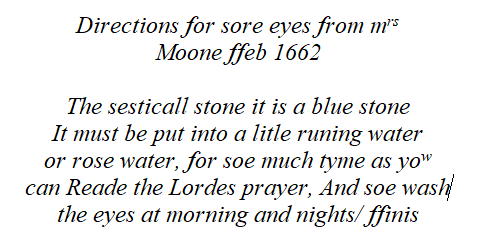

The writer is literate, familiar with the Bible and interested in medicine. The cure is one of many contained in John Gwin’s Commonplace Book and hints at the rich, fascinating content of the volume. It is arguably one of the most important sources that exists for medicine in seventeenth century Wales but contains much more besides.

John Gwin is undoubtedly the author but which one? There were at least five of that name in the family at Llangwm Uchaf between 1591 and the beginning of the eighteenth century. The span of the book exceeds a century and is clearly not the work of just one person but it is likely that the main author is John Gwin III who was born circa 1610-1620, and died in the 1680s.

The book is small, bound with limp vellum covers that have been reinforced with boards inserted later. It is written from two directions; one end begins with the accounts of William Parkes, John Gwin's brother in law, in the early 1630s, while the other begins in 1642 in a different hand, possibly that of John Gwin’s father, John Gwin II. The contents of the book are so varied as to defy concise description. It doesn’t call itself anything. The term 'Commonplace Book' was applied by the very fortunate cataloguer in Newport Library who was assigned the task probably in the late 1930s. Rather poignantly, the donor called it simply ‘the old book’. She appears to have been a descendant of John Gwin and we can imagine the revered old book handed down from generation to generation. It was transferred to the Monmouthshire Record Office in 1952.

It is not a diary; neither is it a journal though it may share some of their characteristics. It is a store of notes, records and references, a kind of scrapbook of random writings arranged neither chronologically nor by theme. Perhaps the book’s main characteristic is its diversity.

For a literate person writing things down helps establish control of one’s affairs. Through writing you could fix things for future reference – to settle a dispute, for example.

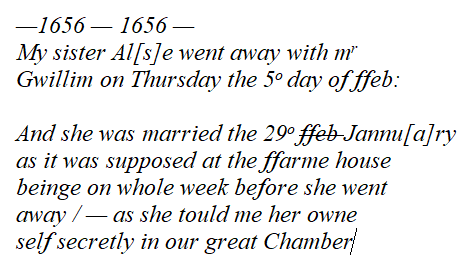

Is John Gwin mindful of potential tittle tattle concerning his sister’s reputation? At least HE knows she was married before going away with Mr Gwillim.

Gwin is an omnivorous gatherer of information, news and wise old sayings. He is insatiably curious. Much of what he records is practical but often it is captured simply because it interests him. At times the entries bear an introspection reminiscent of diary writing but the volume does not have a chronological flow. The sheer randomness of the contents is an essential part of its charm. For example, John Gwin’s first entry in the book after Parkes’s accounts is ‘5 qualifications indispensably requisite in persons that makes wise choyce in marriadge’. (You’ll have to read the book to find out what they are!)

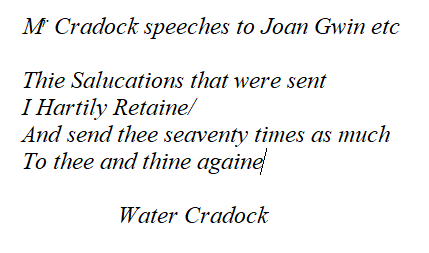

And then in 1668, Gwin records a rhyming message from the preacher Walter Cradock to his wife Joan (who was probably Walter’s cousin).

However, future referral certainly explains many of the entries, be they medical recipes, accounts, tips on good husbandry or the leases on properties. There are things he needs to remember – for business, for health etc.

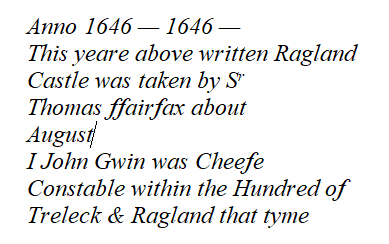

The 1640s through to 1655 was a dramatic period in John Gwin’s life and probably influenced him to start committing occurrences to paper. He may have taken possession of the notebook from his father. He married Joan Cradock in 1641 thus linking him closely to a leading Independent family in the area. His father died in 1645 and his mother in 1647. He records the loss of two sisters and a brother between 1640 and 1645 too. He is Chief Constable of the Hundred of Trelleck and Raglan in 1646 and later held the same office for the Hundred of Usk. His only commentary on the political and military turbulence of the period is a comment made in 1646:

In 1652 he spent £341 purchasing the Poulth or Pwll in Llangwm from Richard Jones The property was a considerable hall house, possession of which may denote a member of the lower gentry but equally it befits a yeoman. Gwin penned an inventory of the property in 1665 when it boasted a kitchen, a little buttery, a loft, a woodhouse, a hall and significantly, ‘a study with 5 planks made up in that chamber for to hold books being in the great chamber’.

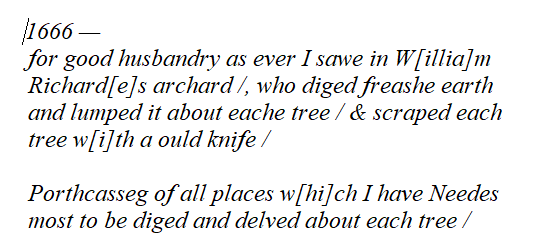

Gwin’s father died in 1645. He had overseen the iron and rod works in Tintern on behalf of the earls of Worcester and he was steward to Anne, the Dowager Countess of Worcester. It is likely that John Gwin III continued in the service of the estate though he is certainly not idle on his own properties. In particular he is an avid planter and grafter of orchards and always looking to improve his methods.

As the only male heir, John Gwin must have inherited a substantial sum when his father died in 1645 for he appears to have been wealthy and owned much land in Llangwm Ucha and possibly elsewhere. Many entries record the collection of rents and these may have been due on properties he owned but some of them may have fallen upon the properties owned by his employer.

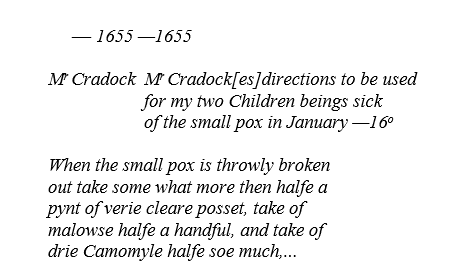

Newly married and holding a key shire office, Gwin became the father of four children born between 1642 and 1651. It is concern for two of his children that prompts the first medical entry in the book and it strikes the reader with stark force:

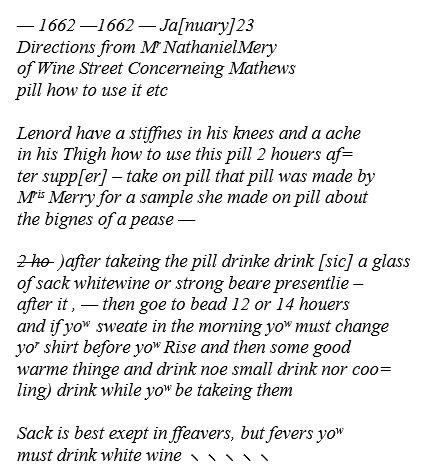

The ingredients and measures are detailed with great care. Both children survived either due to the cure or chance and this may be the reason for his continuing to record medical recipes thereafter. These he acquires from all sorts of places. On one occasion he travels to Bristol to obtain medicine:

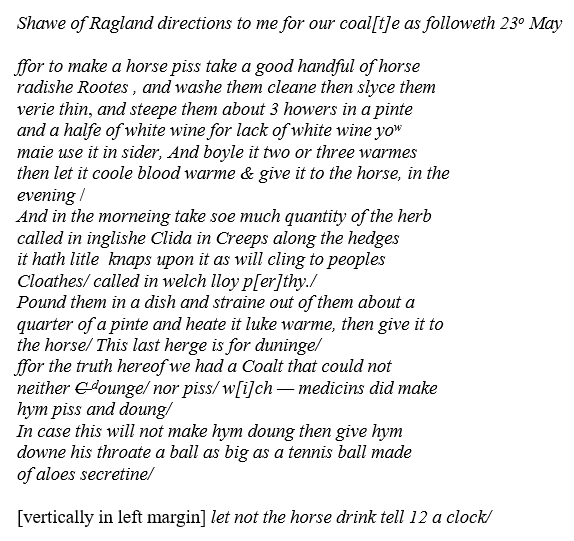

But he also looks for cures close to home. In 1665 he records a treatment to make a horse ‘piss and doung’:

The cures recorded by John Gwin show a combination of traditional and modern medical ideas particularly those relating smallpox and sore eyes.

Medical thinking was in flux during John Gwin’s time. Traditional treatments rested largely on the Galenic system of ‘humours’ with illness thought to come from a humoral imbalance. A cure had to restore the balance, often by purgatives and bloodletting. New theories were emerging and particularly influential on John Gwin was Helmontianism. Helmont’s cures owed much to the new science deriving from chemical and medical experiments of the time.

Helmontianism did not replace tradition. The two sat side by side in John Gwin’s world and his commonplace book provides evidence of both continuity and change in medical practice. The herbs recommended for curing smallpox are traditional, the herb mallow commonly used as a purgative consistent with Galenic tradition. Other cures are more radical.

By 1671 John Gwin is a churchwarden at St Jerome's, Llangwm Uchaf, a role which places him at the heart of church administration. Two lengthy passages in the book reflect this.

1. A copy of an Agreement of 28 February 1671 for ‘settling each particular part of the Church wall yard from the style around the Church porch according to the suns going about to the westward’ and describing the portions reparable by each person.

2. ‘Langum Ycha. For as much as divers variances quarrels and debates and suites of laws to utter destruction and overthrow of manie have heretofore been made and stirred between the inhabitants and parishioners of the said parish of Langum by Reason of inordinate misplacing and intruding of themselves into the seetes of others in the said Church through their ignorance in not knowing their due and rightful places because of their places as being absent dwelling out of the said parish etc’. Then are described the seats in the Church and their rightful occupiers (1671).

John Gwin’s legacy is a rich and important one. Not only has he left us a vivid insight into medical practice and belief in a period of significant transition but he has given us a detailed and poignant portrait of life in a small country parish in seventeenth-century Wales. We identify with the anxious parent when his children get sick; we understand his delight at grafting and planting new orchards and especially when he finds a way to improve his methods; we smile wryly at the seating dispute in his local church. John Gwin has left us treasure indeed in his ‘old book’.

The original of John Gwin's Commonplace Book is held at Gwent Archives, reference D43/4216. The image from the book (smallpox cure) is reproduced here with thanks to Dr. Lisa Snook, Archivist.

Our sincere thanks to Tony Hopkins for allowing us to reproduce his lecture, and to Dr Madeleine Gray for her assistance with this project.