Published: 21/09/2021

Updated: 03/06/2024

Matthew J. Champion MA, FSA, is an archaeologist, historian, author, historic graffiti expert, lecturer, and heritage consultant.

You can follow Matthew on Twitter @medievalg and @mjc_associates.

Every church tells a story. Some are the stories that we all know. The tales of rich families, great deeds, and famous names. The stories that are written down in books, or told in the marble and alabaster monuments on the walls. But every church tells a story, no matter how humble the building, or how humble the story. A trained eye can unravel those stories, and break down a building, construction phase by construction phase. We have learnt to peel back the layers, and strip down even the greatest church to its constituent parts.

But churches are about more than building phases. About more than the difference between Romanesque and High Gothic, Tudor rebuilding and Victorian restorations. Fundamentally they are about people. About the individuals who built them, those who prayed and worshipped within their walls, and ultimately, those laid to rest within the church – or God’s Acre outside. And these stories are there too to be read, no matter how humble and seemingly unimportant. They are there on the walls themselves, hidden in plain sight amongst the graffiti.

Caldecote isn’t a great church. It boasts no magnificent spire, or wealth of stained glass, and despite the survival of its truly beautiful medieval font, the interior is an expanse of plain lime-washed walls. It is modest in so many respects, and even the village that it was first built to serve has long since been deserted and abandoned. Yet even here the walls – and even the floors – still have a story to tell, if you just take the time to look closely.

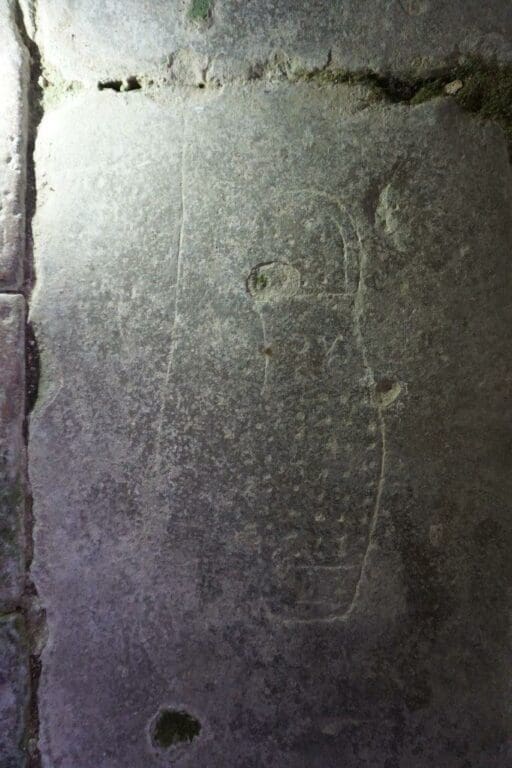

Here at Caldecote much of the history is literally beneath your feet. If you look down as you enter the porch you will see several outlines of shoes carved into the stone floor. A few of them are distinctly different in style than your own shoes, with squared toes and clear lines of hobnails – all of which help date them to the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. Although several of the shoe outlines are now badly worn it is still possible to make out pairs of initials carved into each – the initials of those who traced around their own shoe many centuries ago. A close examination will also show you that the shoes are not alone on the floor, and although now almost lost, you can clearly make out the outline of a hand.

Leaving such marks as these shoes and hand outlines on a building has been taking place for thousands of years - with ancient echoes stretching right back into prehistory, and the earliest of cave paintings. In many cases, they are left by the craftsmen working on churches and are often to be found etched into the lead of the roof as a memento of works carried out. In other cases, such as here at Caldecote, they may have been left by visitors to the church, or members of the congregation. Everyday people just wanting to leave their mark, and commemorate their visit.

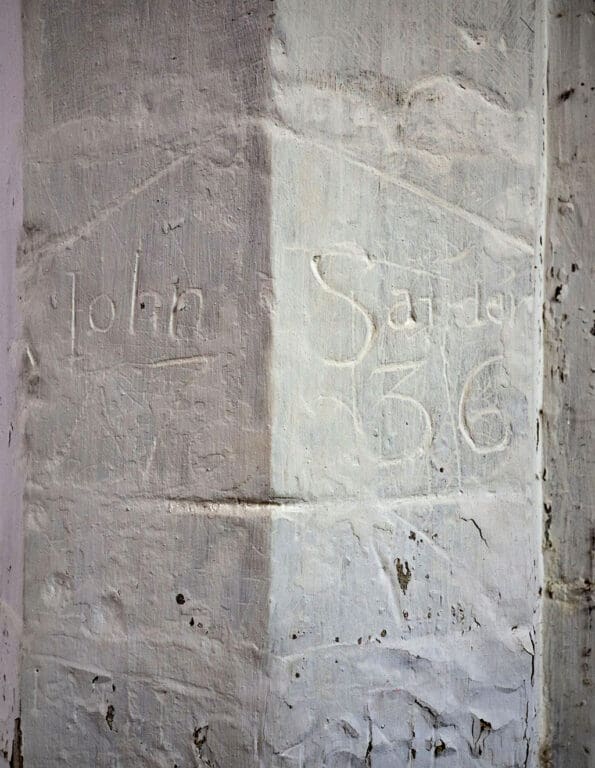

In some cases these names and marks can convey more than just a memory of a visit and the few minutes or hours spent carving the stonework. On the base of the tower is a neatly cut inscription, reading simply ‘John Sanders 1736’, all set within a carved frame that takes the form of a rectangle set beneath a pitched roof. These types of inscriptions are found across the country, although few are as neatly carved as the example here at Caldecote. They begin to appear at about the same time as the elaborate wall monuments for the dead, and it is believed that many of them were created to act as informal memorials. Commemorations for the dead who couldn’t afford the fine marble and alabaster, and perhaps even a gravestone. In some cases these inscriptions may be the only mark this particular individual left on this world. No small irony in a church such as here, where most monuments have long since been removed, but the humble marks on the walls remain.

And it isn’t just the relatively recent memories of workmen, and commemorations of visits, that are found amongst the graffiti. Even in a modest church like Caldecote you can come across faint markings that hark back to the Middle Ages. Ghostly echoes of the congregation who once filled this building, leaving marks of their faith and devotion scratched into the stonework itself. On the stonework at the base of the tower can be seen an elaborate knotwork design – sometimes referred to as a ‘pelta’ or ‘Solomon’s knot’. This symbol isn’t exactly common amongst medieval church graffiti, but it is found elsewhere in church architecture and decoration. In England its use stretches all the way back to the twelfth century, when it was seen as an alternative to the cross or crucifix.

And these aren’t the only marks to be found here. If you take the time to look, you will see that the base of the tower, and the walls of the fifteenth century porch, are all covered in a mass of markings. Initials, dates, crosses, compass drawn designs – all jostling for space next to the lime-wash, which undoubtedly covers over many other examples. Even the rather glorious late medieval font hasn’t completely escaped attention, with graffiti nestling between the crisp lines of the carving. A memory of a time when this humble church bustled with people.

Why then were the people of medieval Caldecote carving graffiti into the stonework of their church? Was it considered an act of vandalism that would have brought down the condemnation of the parish priest? It would appear not. Whilst we today regard graffiti as a form of anti-social behaviour, the evidence shows that this wasn't the case in the Middle Ages. Indeed, a close examination of the graffiti inscriptions in many of England's parish churches reveals that everyone was doing it - including the Lord of the Manor, and even the parish priest himself. And many of these markings, such as the little Pelta designs at Caldecote, were actually devotional and religious in nature. They were no less than prayers made solid in stone. Prayers that the observant visitor can still make out to this day, long centuries after those who created them are dust.

Photographs of Caldecote church, its Solomon’s knot and John Sanders graffiti marks © Adrian Powter.