Published: 23/03/2022

Updated: 11/09/2023

Before the early 1900s, a handful of women dared to fill the traditionally male positions of Parish Clerk and churchwarden. This included Mary Flint, who held the post of parish clerk at St Mary’s, Caldecote, Herts from 1820-1838.

The rarity of ‘female parish clerks’ made them newsworthy, and the public reacted to them with amazement, admiration, amusement, or dismay. In this blog, we take a journey through historical newspapers to find out more.

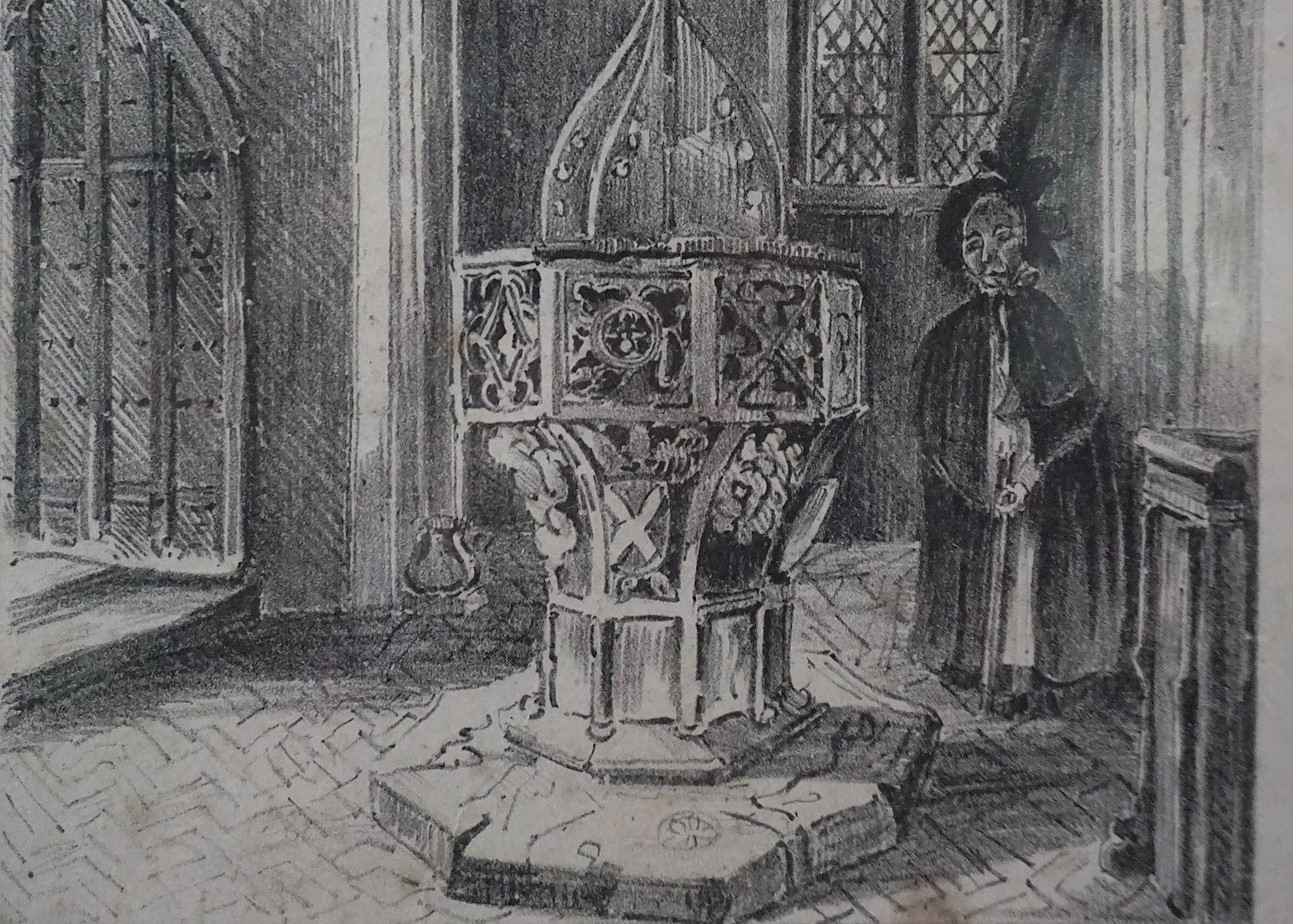

In the early 19th century, St Mary Magdalene's in Caldecote, Hertfordshire had something quite remarkable — a female parish clerk. Mary Flint held the post for 18 years at a time when it was extraordinary for a woman to do so. In Mary’s case, she filled the role after the death of her husband John, who had served as parish clerk for many years. Mary was seen as a curiosity, but she was also applauded for being ‘quiet and cheerful in manner – steady and persevering in duty – at home, active and affectionate – as a Christian practical and pious.’ Mary continued in the role until her death in 1838, aged 82. And in 1841, the Church of England Magazine published a description and sketch of 'the female parish clerk and font' of Caldecote.

I wondered just how rare it was for women to hold parochial positions before the 20th century. How many women like Mary Flint had broken ground by taking on these conventionally male roles, how were they perceived, and how long would it be until the fact of a female parish clerk was no longer newsworthy?

But first, what exactly were the qualifications and duties of the parish clerk?

According to Mark Pearsall, in a talk for the National Archives: ‘the parish clerk was appointed by the rectoral vicar and acted as his clerk and sometimes as clerk to the vestry. He assisted at the church services and led the responses and in some parishes he would act as the sexton as well and actually dig the grave and … maintain the churchyard. He might sometimes make entries in the parish registers, but he wasn’t supposed to.’ The parish clerk was something of a dual role, having both clerical and practical responsibilities.

Other essential parochial dignitaries included churchwardens and the overseer of the poor. In past centuries, churchwardens (most parishes had two but many had more) had a wealth of responsibilities. They oversaw the maintenance of the parish church and kept accounts of income and expenditure. They managed pew rents and assignments, presented misdemeanors of parishioners to ecclesiastical courts, submitted copies of parish registers to the diocese and acted as witnesses for many legal and ecclesiastical events. The overseer of the poor managed the collection and distribution of poor relief in the parish and held the authority to determine who was eligible for, and deserving of, support.

Both clerks and churchwardens had clerical and practical responsibilities. It was necessary for both to be literate. A crucial difference was that while churchwardens were volunteers (willing or unwilling), the parish clerk was a paid position. Income was often a combination of a quarterly or annual salary and additional fees for services performed in the church (such as marriages, burials, churching of women, bell-tolling, and laundering of clerical garbs). Additional perks of the job included receiving two eggs for every cock in the parish at Easter. Because of these monetary and other benefits, the parish clerk was often satirised as having a high opinion of himself. However, in poor country parishes, the pay was very paltry.

The qualification to holding any of these parochial offices was ownership of property. And male property owners were expected to fulfill this duty when called upon, or be subject to a fine. Women could own property (though before 1882 only if they were widows or unmarried), but ‘if a female householder became liable for appointment, the office was usually held by a male substitute who was appointed on her behalf’. However, there were a few exceptions.

It's difficult to find firm evidence of women in these roles, especially before the 19th century. They might be mentioned in parish records (if the records have survived), and very occasionally there is evidence in churches themselves. At Caldecote, Herts, a metal plaque inscribed with 'Katherine Morris 1736' is displayed on the roof. A similar plaque bearing the name of 'Dinah Holme 1780' can be seen alongside the names of male churchwardens at Skeffling in East Yorkshire. Could they be clues that these parishes had female churchwardens in the 1700s?

19th century newspapers are a rich resource for reports of women parish clerks and church wardens — both contemporary appointments and stories from earlier times. From these sources we know that when women did occasionally act as parish officials, they were met with amazement, amusement, or disapproval by fellow parishioners, authority figures, and newspaper readers nationwide.

The earliest mention of a female churchwarden I came across in newspaper records was in a review of an ecclesiastical history written in 1885, which stated that ‘in 1580 there was a female churchwarden in Tintinhull, who cut up the cope to make an altar cloth’.1 Was this apocryphal? It certainly seems like a joke that might be made about the foolish actions of a woman in that position.

Next, we zip forward two centuries to the 1770s, a few decades before Mary Flint was diligently performing her duties at Caldecote — when Ann Canon served as the parish clerk at Pitchcott, Bucks. ‘In October 1772, she received the sum of 4s. “for sarving 9 weeks as clark.” Two years later her name appears again in the register for the same amount, from which time, down to 1779, she appears to have fulfilled the office regularly for 6s. per quarter.’ But by 1818 a man had stepped into the role and ‘received a guinea “for saying Amen.” When the Bucks Herald shared this story in 1890, the writer said he’d never come across another instance of a female parish clerk and added, ‘If any of my readers know of similar instances of female clerks I shall be very pleased to hear of them.’2

Another example of a female parish clerk prior to Mary Flint was found In Totteridge (historically in Herts; now in the London borough of Barnet). On 2 March 1802, the burial register recorded the remarkable service of ‘Elizabeth King, widow, for forty-six years clerk of this parish, in the ninety-first year of her age.’3 And contemporary to Mary Flint, there was a female parish clerk in Sudbrooke, near Lincoln, in 1830 (her name unknown). ‘She was still in the service of the church when she died, after giving great satisfaction by the way in which she performed her duties.’4

The various parish roles came under scrutiny in 1830 in the case of Fitzgibbon v. churchwardens of St. Andrew’s parish (in Dublin). It seems that the churchwardens had ceased to pay the sexton of the parish a salary, leading to a heated discussion over whether the sexton should or should not be a paid role, and whether it was truly distinct from other offices. The argument was put forward that the sexton’s and parish clerk’s duties could not practically be performed by the same person since ‘The sexton had to open the pews - it was the duty of the clerk to make the responses. Was the clerk while doing so to go and open the pews for the parishioners, and having opened them, was he to go back and sing a psalm?’ (This farcical picture provoked laughter in court). Moreover, it was argued, ‘A woman might be a sexton, or a sextoness, but he believed that there was not any instance of a female acting as parish clerk.’5 Clearly, they were unaware of the precedents already set by Ann Canon, Elizabeth King and Mary Flint.

The circumstances that had led to Ann Canon and Elizabeth King being appointed as parish clerk are unknown, but a situation arose in Norfolk, 1842, that left the parish with no choice:

IGNORANCE IN NORFOLK

It was stated at the annual meeting of the British and Foreign School Society, held in London last week, that, in a place in Norfolk, such was the ignorance of the population, that a female had officiated as parish clerk for the last two years, because none of the adult males were able to read.6

Although originally cited as serious evidence of the need for increased access to education, the anecdote was shared in a column of ‘Collectanea’, along with the discovery of a huge bone-filled cave in Spain, and the theft of an Eton master’s snuffbox by jackdaws.

In Birstall, West Yorkshire, 1843, a woman appointed herself churchwarden simply because noone else stepped up to take it on:

A FEMALE CHURCHWARDEN - A notice was attached to the door of Birstal church, on Sunday week, called a vestry meeting in the usual way, to elect a churchwarden for the ensuing year. At the time appointed, the wife of the assistant overseer entered the Vestry with the parish book in which the usual entry is made on such an occasion, and after waiting nearly an hour and no person making his appearance either lay or clerical, the good dame took her departure and budged home with the book under her arm. On entering her dwelling, her husband eagerly enquired who was appointed warden, to which she replied, why me to be sure — thee, ejaculated the astonished official, yes, me, reiterated the wife, for there has not been another living soul at the meeting, therefore, I suppose, I must be churchwarden.7

The tone of the article makes it hard to ascertain whether the 'good dame' had indeed taken on the position, or simply provided newspaper sellers with an amusing tale.

Sadly, the novelty of a female parish clerk or warden did elicit ridicule at times. In 1846, Mrs Edwards gave evidence before a committee of the House of Commons that was investigating the idea of building the Newport, Abergavenny, and Hereford Railway. Newspapers gleefully reported on her humiliation in yet another article titled ‘FEMALE PARISH CLERK’:

Mrs Edwards was examined as a witness. She said she was parish clerk of Llanvihangel-juxta-Usk. (A laugh). She did not go into the place where her husband, the late parish clerk, did, and give out the responses. (A laugh). In other points she filled the place of her husband.8

In another version of the event we read that ‘Mrs Edwards … in reply to a question, and amidst great laughter, stated that she was parish clerk of Llanvihangel-juxta-Usk. She was proceeding to state the duties of her office, when, by a curious coincidence, which greatly increased the laughter, it was announced that the speaker was at prayers.’9

Mrs Edwards had evidently taken on the clerical aspects of her husband’s position after he died, and had travelled to London to share local knowledge with the committee, but her testimony was met with derision. However, Mrs Edwards clearly continued to serve for many decades, as in 1875 she was in the news again. Ann Edwards (her full name) had sued the churchwarden for her parish clerk salary, and the ‘rather amusing case’ was heard in Abergavenny County Court. The judge’s first recorded words were “A woman a parish clerk?”

Ann’s son Francis testified that ‘his father was parish clerk, and after his death his mother did the work, or at least he did it for her. He rang the bell, and had the communion cloth washed and other things.’ The examination continued like this:

Judge: How can your mother be parish clerk?

Francis: She was appointed.

Judge: How was she appointed?

Francis: By Mr Pritchard the churchwarden.

Judge: How can a churchwarden appoint a parish clerk? It is the duty of the incumbent.

Francis: [not answering the question] Mr Pritchard in 1870 said he would not pay any more.

When cross-examined, Francis reiterated that his mother was the clerk and he was her deputy.

Essentially, Mr Pritchard the churchwarden had made Mrs Edwards the parish clerk (24 years earlier?) but eventually refused to pay her. However, she had continued, with her son’s help, to perform the duties unpaid for two more years.

After interrogating her exact duties and how much she charged for them, Judge Jones summed up: “I am quite certain a woman can’t be parish clerk. It must be a male, above 18 I think. I see no reason, however, why a woman should not be a bell-ringer.” Although Ann had been claiming £2 9s.1d., the final judgment only awarded her 14s.10

The judge at Abergavenny did not seem too sure of the absolute rules around eligibility for becoming a parish clerk (in fact, though in practice the role was filled by a man, there does not seem to have been any legal definition). The solicitor behind the legal advice column ‘COUNTRY AND PARISH LAWYER in Bell’s Weekly Messenger was equally vague in advising a concerned parishioner:

Our correspondent says, “The curate in my parish has chosen a female to be his churchwarden. Is the election legal?”

The law in relation to this matter is exceedingly wide, and as a female may be a house-holder and a rate payer, we are not prepared to say that she may not be a churchwarden; but we think it unseemly and unbecoming to appoint a female to such an office. The Spiritual Court may, if it see necessary, interpose.11

The idea that it was ‘unbecoming’ for a woman to take on a traditionally male role could at times lead to suspicion and superstition. In Willoughton, Lincolnshire in the 1860s ‘there lived a famous old dame named Betty Wells who officiated as parish clerk. For many years she occupied the lowest compartment of the three-decker pulpit reading the lessons and leading the responses. With the exception of ringing the bell she fulfilled all the duties of clerk. Betty was looked upon by villagers as a witch and it is said that she made things very unpleasant for those who offended her.’12

Despite negativity, women did continue to be appointed, and continued to make the news. In 1876, Little Wakering, Essex had a female parish clerk who was also the schoolmistress, and ‘a comely and highly respectable looking dame she is.’13 In 1881, the ‘wandering postman’ (a local gossip column) was informed ‘by the people from the Ogmore that Bridgend can not only boast of a female billposter and a female scavenger, but of a female parish clerk and a female gaffer.’14

Towards the end of the 19th century I observed a noticeable shift in reporting about women parish clerks, to a position of more respect and even pride.

We read of the public offices filled by women, and were patriotically pleased to find that here the British empire leads the way. Nearly one hundred women are now serving on School Boards in England and Wales. Boards in four country districts have women as clerks. Fifty-eight women are serving on Boards of Guardians in England, and seven in Scotland. A few instances are on record of female overseers, churchwardens, and parish clerks, being appointed. Four ladies are on the Metropolitan Asylums Board, one is a Poor Law Inspector, one an inspector of Lace Manufacture in Ireland, and at least six women are filling the office of Registrars of births and deaths.15

This sentiment was echoed on a county level by the Bucks Herald in 1897:

Our Buckinghamshire women are well to the fore in some occupations which are usually considered to belong exclusively to the sterner sex. Years ago they had a female parish clerk at Pitchcott [we heard about Ann Cannon above] … Then in the northern part of the county, at Thornborough the women used to repair to the Parish Church on Shrove Tuesday to ring the Pancake Bell. At Iver a woman has acted as registrar and vaccination officer for several years with the greatest success. At the recent meeting of the Parish Council of Langley, near Slough, the members were amazed at receiving an application from a woman for the univiting post of slaughterhouse inspector.16

The applicant for slaughterhouse inspector didn’t get the job, but times were clearly a-changin’.

Indeed, women were beginning to be appreciated for bringing a different style to the role of clerk. In 1890, the Rev. R. W. Hippisley, rector of Stow-on-the-wold came under fire for ‘the deplorable state’ of his parish. He had alienated his chief parishioners ‘and actually had for this reason to appoint a female churchwarden.’17 It seemed that there was hope that a woman churchwarden might ease tensions. However, before Hippisley resigned in 1899, the townspeople hanged the rector in effigy!

A wider variety of women were also appointed by the end of the century. At Ramsey, near Harwich, in 1896, the vicar ‘nominated Mrs. Isabella Saxbey, a farm labourer, as his warden.’18 And in 1900, the vicar of Great Wilbraham, Cambs, took ‘a new departure in matters ecclesiastical, for he has nominated his wife as Vicar’s Warden for the ensuing year. We know of no rule which makes her incapable of filling the office, and we believe that there are several lady churchwardens in the country. This is, however, we believe, the first time that a clergyman has appointed his own wife to the office.’19

Within the first few months of the Edwardian era, a senior clergyman spoke out in favour of female churchwardens. Archdeacon Mount commented that ‘To the office of Churchwarden, it appeared any householder resident in the parish was eligible, male or female: and there were cases in which the parishioners had elected, wisely as it seemed to him, a female as their Churchwarden.' Rather than focus on the gender of the churchwarden he emphasised the responsibility of the role, which was “of great dignity, and great importance. To them was entrusted the care of the fabric of the parish church, at once probably the most ancient and historically interesting building in the parish.”20

In spite of the sea-change, women clerks and wardens were still a rarity, clerks in particular. In 1907 at Penn, Bucks, Miss Benson was elected Vicar’s Warden for the sixth time in succession, as well as churchwarden, by a vestry that was entirely female, with one exception — the parish clerk.21 During WW1, Mrs Collins, parish clerk and sextoness at St James’s, Bath (having succeeded her husband), died — and was said to have been one of only two female parish clerks in the country.22

However, in tandem with the significant progression in women’s rights between the two world wars, women were becoming much more established as both churchwardens and parish clerks by the 1930s. In 1934, the election of a woman churchwarden at Lancing was said to have ‘made history so far as the Rural deanery of Worthing is concerned, but such an appointment is not unknown in these days. It is a modern practice.’23 In 1941, the Boston Guardian paid tribute to churchwardens ‘for it must be remembered that not one of the 25,000 men and women (for the female churchwarden is not the rara avis she used to be) entering upon this ancient office receives any remuneration for services rendered.'24 And in 1943, Wivelsfield parish council in East Sussex advertised for ‘the services of a clerk (male or female).’25

By 1977, the headline of ‘FEMALE PARISH CLERK’ was only a distant memory. When Miss Winifred Parker was unanimously elected that year to be a churchwarden at St John’s, Manthorpe, Lincs, the news headline reflected the parish’s feeling that this was long overdue. Winifred’s face smiled out from the page beneath the headline: ‘At last, a woman churchwarden’.26

If you enjoyed this article, there are links to more blogs about pioneering women below. We also recommend The Sextoness of Goodramgate, a blog from the Borthwick Institute of Archives at the University of York.