Published: 11/03/2021

Updated: 05/05/2023

We're immensely proud to share these stories of women who have fought for equality and broken down barriers to become pioneers in their fields.

From the intensely risky and controversial political activism of suffragette Isabel Seymour and scandalous novels of Madame Sarah Grand, to the quiet courage of Mary Flint, who flourished in a traditionally male role, and Ann Walker, who lived and worshipped with the woman she loved, they have helped secure greater freedoms and opportunities for the generations that followed them.

Isabel Seymour planting a holly tree in ‘Annie’s Arborertum’, at Eagle House, a sanctuary for women participating in the illegal militant suffragette movement. (Public domain, via Wikimedia commons)

Marion Isabella Seymour (1882-1968) isn’t a household name like Emmeline Pankhurst, but in the early 1900s she was a prominent activist campaigning for women’s suffrage.

Isabel Seymour (as she was usually known) was introduced to the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) by her friends and prominent suffragists, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. She joined the organisation in 1906, initially working from its London HQ as Hospitality Secretary, assisting women visiting London on WSPU business. She later took on the role of Prisoners’ Secretary.

In 1909, the PR-savvy WSPU launched their ‘Suffragette bus’, decked out in white, purple and green and driven, by women, around the West End. Immediately following on from that, Isabel Seymour drove a press cart decorated with flags in the same colours, delivering copies of Votes for Women from the WSPU’s offices in Clement’s Inn.

Seymour seems to have been particularly valued as a speaker, especially as she was fluent in German. She took a number of trips to Europe before WW1, including Germany, Austria and Russia, to speak at meetings with women’s suffrage organisations in those regions. According to coverage of her trips in Votes for Women, Isabel was the first to speak to those groups about the militant methods adopted by the WSPU. In some areas, she found women’s struggles to be almost fifty years behind England, and ‘almost hopeless’; ‘In Austria, as in Germany, all the women’s hopes are concentrated in the English suffragettes. “When once the English women are free,” they say, “our freedom comes into sight.”’1

Isabel seems to have been imprisoned for her activism, but the details of this are unknown. However, in 1909, she was invited to Eagle House, which was known as the Suffragettes’ Retreat. It was owned by the Blathwayts, including mother and daughter suffragettes Emily and Mary Blathwayt, who cared for suffragettes recovering from harsh prison treatment. Around fifty suffragettes planted a tree there as a symbol of their hope for equality; Isabel Seymour was photographed planting a holly tree on 24 Oct 1909. Sadly, this living memorial was bulldozed in the 1960s.

Seymour spent eight years in Canada and returned to England in about 1920. In 1922, she became the first woman member of Hampshire County Council. Her many years as a councillor included a role in the Education Committee, where she worked to achieve equality for women head-teachers.2

Isabel Seymour was buried at St Mary of the Angels, Brownshill, Gloucestershire, in 1968, aged 85. Before her death, she gave a lively interview about her experiences to Antonia Raeburn, who published The Militant Suffragettes in 1973.

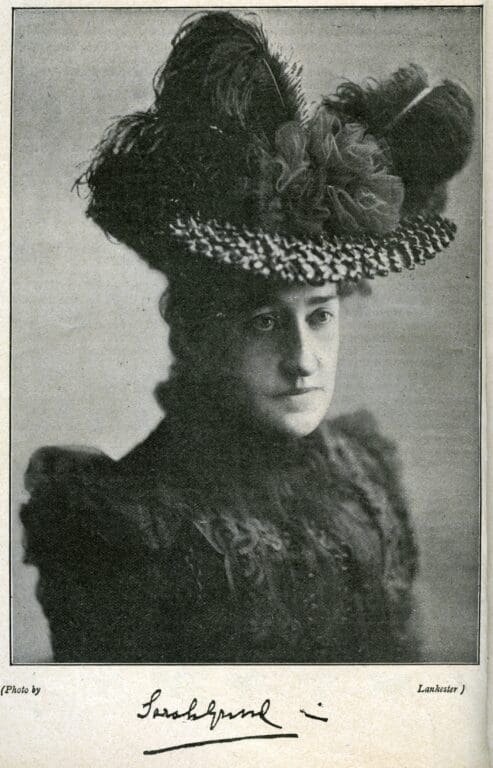

‘Madame’ Sarah Grand was internationally famous (and scandalous!) in her day but has since been largely forgotten. Born Frances Bellenden Clarke, she married at 16 to a much older widower with children not much younger than herself. It was an unhappy marriage, and after leaving her husband, she devoted herself to writing, lecturing on women’s issues and campaigning for votes for women.

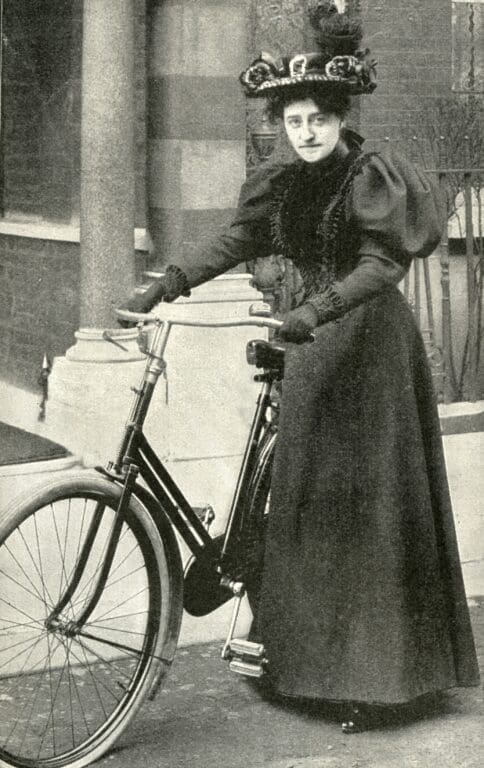

Grand’s novels centred on the ‘New Woman’, a name she coined for educated women who sought independence from oppressive marriages, and greater social freedoms. She promoted women’s cycling, and argued for less restrictive, ‘rational’ clothing, such as split skirts.

‘The Heavenly Twins’, published in 1893, was her first commercial success, selling 20,000 copies — surprising for a story that highlighted the double standards of sexual morality for men and women and the devastating effects of syphilis on families.

Mark Twain reviewed it and declared that “The grammar is often dreadful, but never mind that, it is a good strong book”. Sarah’s writing made her a heroine for many women but also ostracised her from a lot of the people in her social circle.

Sarah Grand’s family lived at the Manor of Rysome Garth, less than two miles from St Helen’s, Skeffling, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, where her parents were buried. A speech she once gave on churches gives a clue to her feeling about the family’s church … “If they had never been far away from home they could have no idea about the way the heart softened and expanded at the recollection of the little spot of earth which they had been taught from their earliest childhood to believe was holy ground.”

However, by the end of the century, St Helen’s was, as now, in need of restoration. The roof was replaced in 1901, but the south wall was still in a dangerous condition. So on 11 March 1902, Madame Grand, the ‘popular authoress’, gave a lecture in Hull to raise funds for Skeffling parish church, with the vicar in attendance.

Grand ‘scattered pearls of wisdom freely’ for a ‘delightful, if fatiguing’ (!) hour and a half, exploring the theme of memory: “things we are glad to remember, things we are afraid to remember, things we regret to remember and things we forget to remember”.3

In 1920, Sarah Grand moved to Bath. The city's new mayor, elected in 1922, had no wife to perform the traditional duties of Lady 'Mayoress', and Grand was asked to take on the post as an independent woman — a role which she filled three times. Grand was so popular that she was encouraged to stand for Mayor herself, but declined. In WW2, Sarah Grand’s house in Bath was bombed and she moved to Wiltshire for safety, where she died in 1943 at the age of almost 89.

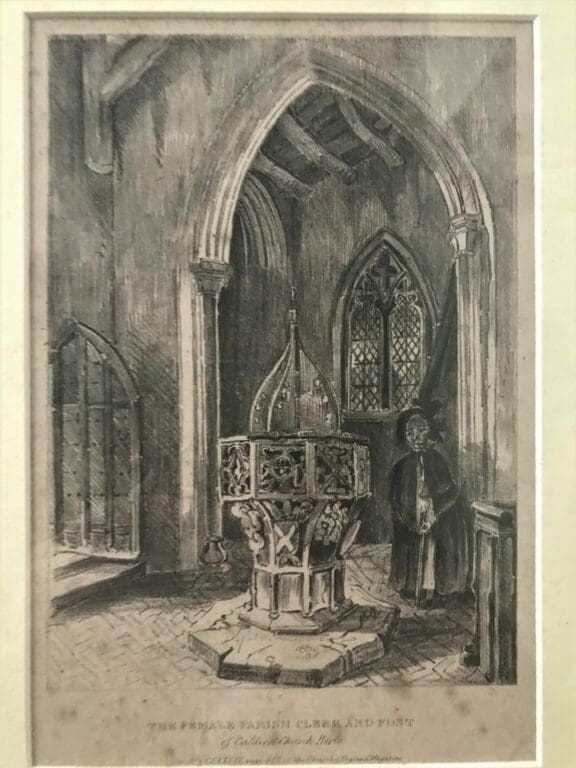

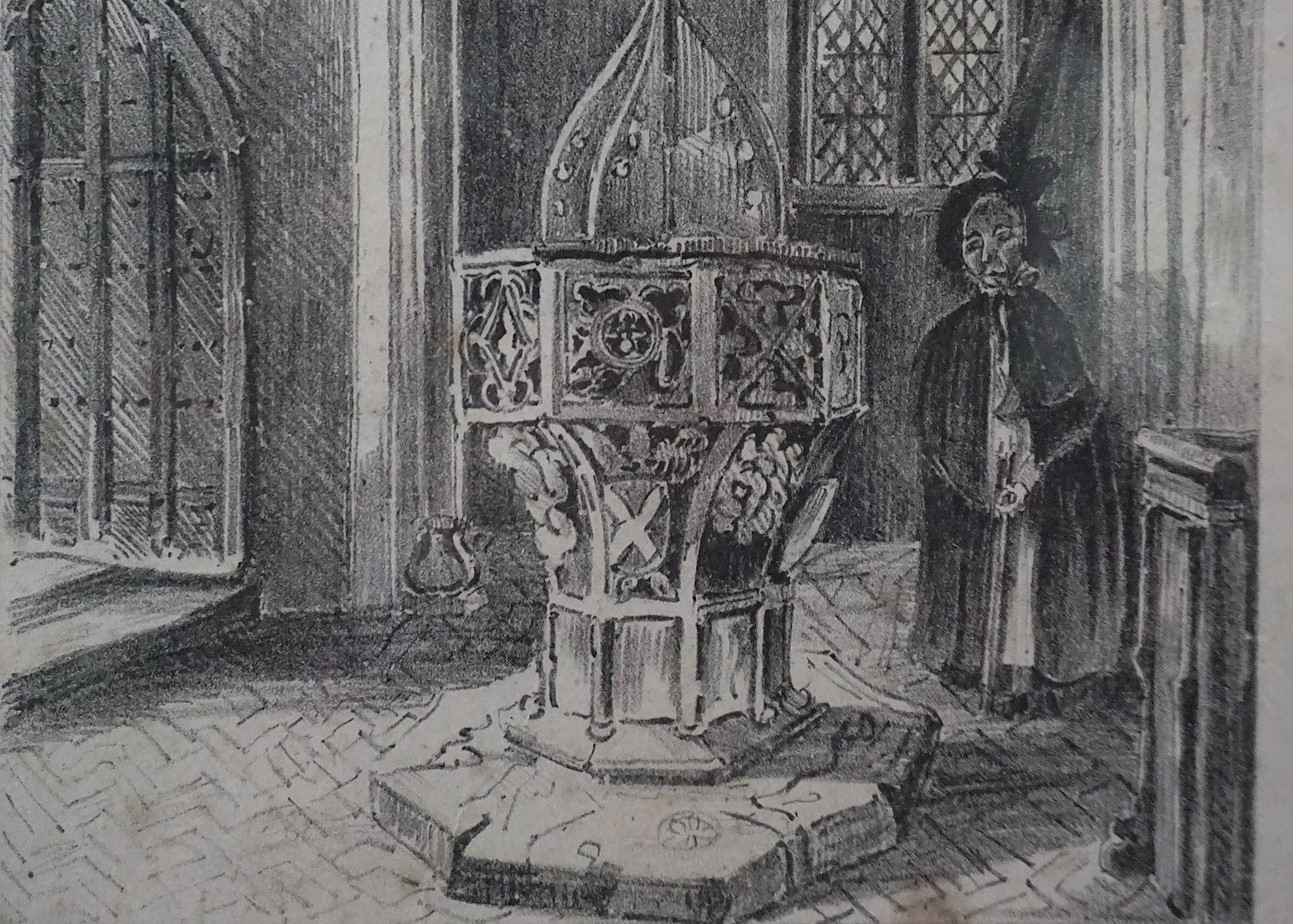

The May 1841 edition of the Church of England Magazine contained ‘many orthodox sermons of exceeding dullness, many vigorous denunciations of the Bishop of Rome’ and an interesting feature on a woman called Mary Flint, ‘the female parish clerk of Caldecote, Hertfordshire’.

Mary Flint nee Street was born in Caldecote in 1755 and married her cousin John Flint in 1774. They had 19 children! The family lived rent-free in the parsonage; in exchange, John performed the duties of parish clerk. However, in his sixties, John fell severely ill…

So, Mary proposed that she would take her husband’s position as clerk. This was extraordinary: at that time, under canon and civil law no female could hold this office. But the vicar obliged, and after John’s death in 1818, Mary became a parish clerk — at the time the only female parish clerk in the Church of England.

Every Sunday for 18 years, Mary could be seen in the clerk’s desk at Caldecote church, her dress old-fashioned, her ‘cap and hood drawn closely round her venerable placid countenance’. Her manner was perfectly composed, her enunciation clear and distinct. She was ‘quiet and cheerful in manner – steady and persevering in duty – at home, active and affectionate – as a Christian practical and pious.’

In the 1830s, a new clergyman took the living at Caldecote. When going to meet his parish clerk for the first time, he was astonished to see Mary Flint sitting on the stone seat in the porch. Mary’s health was by then in decline and her granddaughter now accompanied her on duties.

In the 1830s, Mary was sketched by Charlotte Morice, daughter of the rector of nearby Ashwell (and an artist, school founder and supporter of women's rights). Mary was captured for posterity in her tight cap and hood, holding a walking stick and standing by the 15th-century font at St Mary Magdalene's, Caldecote.

Mary served until her death in 1838, aged 82. She was buried in the south side of Caldecote churchyard to the left of her husband, and thus closer to the church; they share a headstone.

Mary had an eminent great grandson: Thomas Inskip, the first Viscount Caldecote (1876-1947). He was Minister of Defence from 1936 to 1939, Lord High Chancellor 1939-40 and Lord Chief Justice of England 1940-46.4 You'll find Lord Caldecote in the history books.

However, Mary's own unique pioneering story could have easily been lost to time. How grateful we are that Mary Flint’s life and likeness were recorded.

Caldecote church may have also had a female church warden or lead worker in the early 1700s. Read about Katherine Morris in Craftswomen and Artists.

Read about other women who dared to serve as parish clerks and churchwardens from the 1500s to the early 1900s in "A female parish clerk?!"

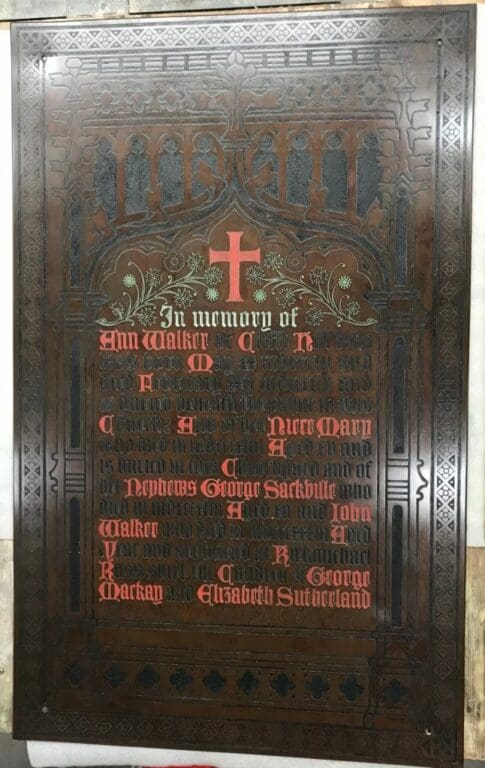

Ann Walker’s memorial, recently restored in a project coordinated by In Search of Ann Walker

Old St Matthew’s tower in Lightcliffe, West Yorkshire came into our care after the Georgian church of St Matthew’s was demolished in the 1960s. Only the tower remained.

St Matthew’s church and tower were still new when the Walker family of Lightcliffe, founders of the church, baptised their third daughter, Ann Walker, there in 1803. Twenty-five years later, after the death of her parents, and her brother’s sudden death on his honeymoon, Ann and her sister Elizabeth inherited the family’s estate, Crow Nest (less than a mile from St Matthew’s). At around the same time, in nearby Halifax, another heiress, Anne Lister, known locally as ‘Captain Tom Lister’ (and later ‘Gentleman Jack’), took charge of her family home, Shibden Hall.

Ann and Anne had known each other as neighbours for some time, but in 1832 they fell in love, sealing their union in Holy Trinity Church, Goodramgate, York in 1834. This pioneering married couple lived together at Shibden Hall, but they attended church in more welcoming Lightcliffe — where they shared a green velvet-lined box pew — until Anne’s untimely death in 1840.

Ann Walker spent the end of her life in Lightcliffe and was buried under St Matthew's church in 1854. Her brass memorial plaque now hangs in the tower, and has recently been restored. A small plaque has also been installed by the Friends of St Matthew's Churchyard, Lightcliffe to mark the location of her grave.

Anne Lister's coded diaries have become recognised by UNESCO for their outstanding importance to UK heritage. In October 2020, Ann Walker's own voice was heard for the first time, when her journal was identified in the West Yorkshire Archives by volunteer research group In Search of Ann Walker.

Read more about Ann Walker and Anne Lister and their deep connections to St Matthew's, Lightcliffe in a guest blog by Friends of St Matthew's Churchyard chairman Ian Philp.

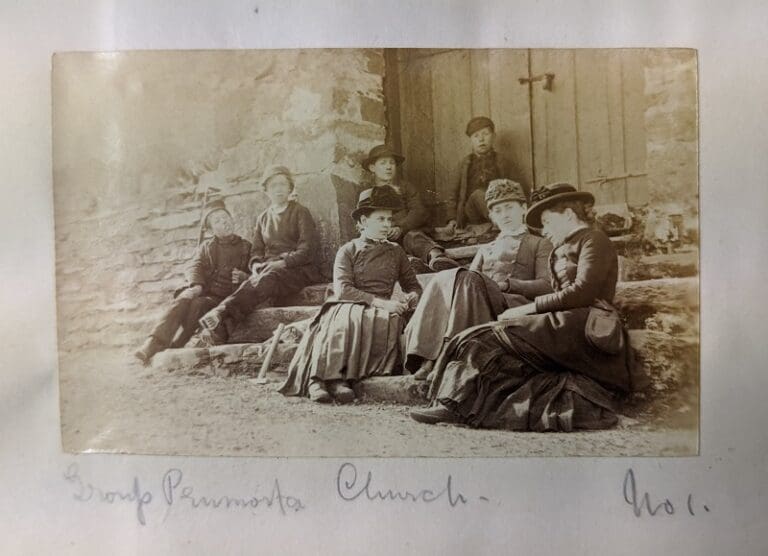

The Sedgwick Club’s women associates on the steps of Penmorfa church (Photograph in the Archives of the Sedgwick Museum and reproduced here with permission)

In early spring of 1885, three smartly dressed women relaxed on the steps of the 17th century slate lychgate at St Beuno’s, Penmorfa. Gwynedd. They had come to Wales from Cambridge with the Sedgwick Club, a new student geology society.

Women were not yet permitted to be members, yet recent graduates Beatrice Taylor and Ellen Stones, with the help of professor’s wife Mary McKenny Hughes — an experienced ‘amateur’ geologist — were keen to study the fascinating and globally significant geology and palaeontology at Penmorfa.

All photographs of Madame Sarah Grand have been licensed from the Bath In Time image library.